Colonel James Morrison’s frustration inside the command center of Nellis Air Force Base encapsulates a larger threat. His F-35 squadron sat grounded, it’s not because of mechanical issues, but because the depot had run out of critical magnets. The problem lay not in Nevada, but in Beijing. China, wielding its monopoly over obscure but essential minerals, had tightened the valves on the materials that power Western warfare.

For over a decade, the United States and its allies have relied heavily on China for rare earth elements critical to advanced military hardware. These minerals, while arcane to the public, form the invisible scaffolding of modern defense systems. Without them, missiles don’t guide, stealth jets don’t fly, and satellite systems cease to calibrate.

On April 4, 2025, Beijing imposed new export restrictions on a group of seven rare earth elements and their derivatives materials that form the backbone of magnet-based systems essential for both civilian tech and military applications. This was no routine policy tweak; it was economic statecraft, executed with surgical precision.

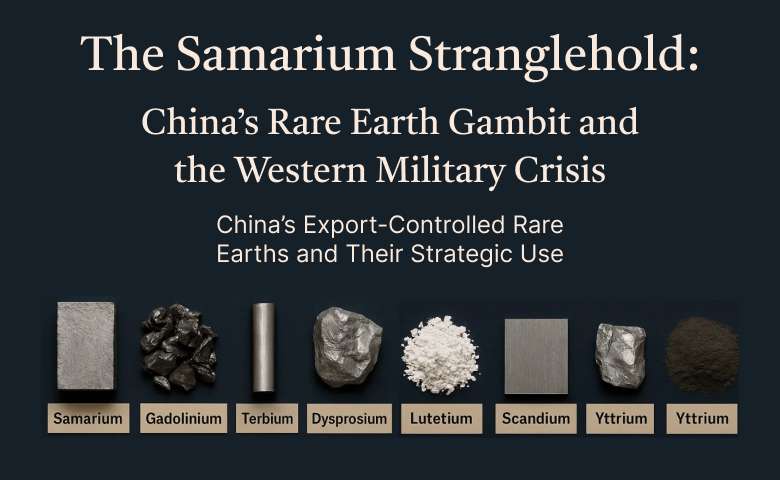

The Controlled Elements: Strategic Materials Behind Beijing’s Leverage

The newly restricted substances span metals, alloys, oxides, and magnets built from the following:

- Samarium – Used in high-temperature resistant magnets found in missiles, fighter jets, and optical lasers. Samarium-cobalt magnets are vital in conditions where ordinary magnets fail, including within nuclear reactors.

- Gadolinium – Key in electronic components, data storage, and MRI technology; also functions in neutron shielding in reactors.

- Terbium – Essential to low-energy lighting systems, X-ray enhancement, and thermoelectric devices.

- Dysprosium – Stabilizes magnets for electric vehicles, wind turbines, and control rods in nuclear power plants.

- Lutetium – Critical in hydrocarbon processing, especially for cracking in oil refineries.

- Scandium – Reinforces aluminum alloys used in aerospace (notably Russian MiG fighters), sports equipment, and high-intensity lighting.

- Yttrium – Used in LED lighting, superconductors, lasers, camera lenses, and certain cancer treatments.

Beijing’s controls apply to these elements in nearly all industrial forms—sheets, rods, wires, powders, and, most significantly, thermos-magnets used in precision systems.

Strategic Dependency and Supply Chain Exposure

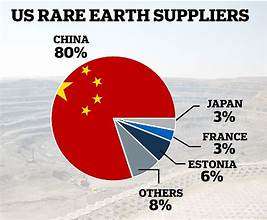

China’s grip over these elements is not accidental. It controls roughly 85% of global rare earth processing capacity. This dominance has allowed it to insert itself as the indispensable node in Western military-industrial supply chains. The U.S., despite awareness of the risk, never fully diversified its sourcing. Samarium, in particular, has become an un-replaceable cog in the defense sector’s gearbox. Its unique ability to retain magnetism at temperatures that would melt lead makes it irreplaceable for advanced missile systems and the high-RPM motors inside F-35s.

China’s grip over these elements is not accidental. It controls roughly 85% of global rare earth processing capacity. This dominance has allowed it to insert itself as the indispensable node in Western military-industrial supply chains. The U.S., despite awareness of the risk, never fully diversified its sourcing. Samarium, in particular, has become an un-replaceable cog in the defense sector’s gearbox. Its unique ability to retain magnetism at temperatures that would melt lead makes it irreplaceable for advanced missile systems and the high-RPM motors inside F-35s.

Lockheed Martin alone uses over 50 pounds of rare earth magnets for each F-35 fighter jet. These magnets are embedded in radar modules, avionics, weapons guidance systems, and actuators. Without them, production halts. The company’s global sourcing teams monitor the flow of these materials obsessively but even the most agile supply chain cannot function without upstream access.

The Biden administration, anticipating this crisis, had authorized two new samarium and sherium production facilities in the U.S. But construction faltered under international trade disputes and local regulatory delays. The result: the United States remains overwhelmingly reliant on Chinese-origin materials.

Weaponizing Trade

Beijing’s official rationale behind the April restrictions invokes international norms, “non-proliferation of nuclear weapons” was the phrase used by China’s Ministry of Commerce. But behind this bureaucratic language is a more potent strategy and asymmetric pressure. The new export rules introduced a licensing system based on end-user verification. Unlike in the past, China can now deny materials not just to countries, but to companies and contractors suspected of supplying weapons to strategic flash points—Taiwan included.

In effect, China now possesses a scalpel it can use to cut through Western military production lines with precision. And it has begun to use it. Several U.S. defense contractors involved in arms sales to Taiwan have been sanctioned, with Chinese firms prohibited from dealing with them financially or materially. While earlier sanctions were porous materials like cerium mixed with cobalt would pass through intermediaries this new regime imposes full-spectrum traceability. The ultimate destination of a magnet now determines whether it leaves Chinese soil.

Geopolitical Repercussions

The immediate consequence has been widespread panic across Western supply chains. Maintenance backlogs are reported not just in the U.S., but across NATO. As European allies scramble for alternatives, Chinese officials and their American counterparts met in London on June 9 to negotiate a path forward. But the diplomatic tables are lopsided.

“I don’t think that’s going to change,” said Michael Hart, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, referring to the new export rules. He’s likely right. Beijing has little incentive to reverse course. These materials offer China rare leverage non-lethal, legally shielded, and globally impactful.

Adding to the complexity is Washington’s own paradox. Department of Defense regulations require that magnets used in military systems be melted or molded within the U.S. or trusted allies. But raw material imports are permitted from any source. That loophole has allowed China to dominate upstream supply chains even as Washington tries to retain downstream sovereignty. It is a regulatory Catch-22 that Beijing is now exploiting to full effect.

Strategic Futures: Control the Minerals, Command the Balance of Power

For the West, the challenge is twofold: securing short-term substitutes and building long-term independence. Some U.S. efforts focus on Australia and Canada for new mining projects. Others aim to revive domestic refining capabilities mothballed decades ago. But nothing short of a multilateral industrial alliance will match the scale and integration China has achieved.

In this era of gray-zone competition, China’s rare earth embargo is not merely a tactical inconvenience. It is a strategic recalibration of global power. By monopolizing materials that underpin the machinery of modern warfare, Beijing has established a form of non-kinetic dominance that bypasses conventional deterrence frameworks. It has exposed the West’s overextended supply chains as its true Achilles’ heel. As defense ministries scramble to localize production and diversify sourcing, the timeline for resilience runs counter to the velocity of geopolitical change. In the calculus of great power rivalry, supremacy will not belong solely to the nation with the most aircraft or missiles, but to the one that controls the molecules required to build them. The frontier of conflict has moved to silent, granular, and elemental. And in this new contest, whoever owns the periodic table may well own the century.