For many centuries the Ganges has been more than a river: it has been a lifeline for identity, a sacred river, the indispensable lifeblood for farm and survival for people across India and Bangladesh. Currently, the Ganges is becoming the epicenter of a new geopolitical storm. The 1996 landmark Ganga Water Sharing Treaty turns 30 in 2026, as India has made it clear that it will not simply roll over the terms of this agreement as it has done twice before. India has proposed to renegotiate the water-sharing agreement with Bangladesh citing increasing domestic requirements, while Bangladesh is currently weathering water stress and riverbank erosion, attributed to climate change. In this fragile moment of diplomacy, millions depend on outcomes shaped more by politics than the river itself.

Ganges Treaty: India – Bangladesh

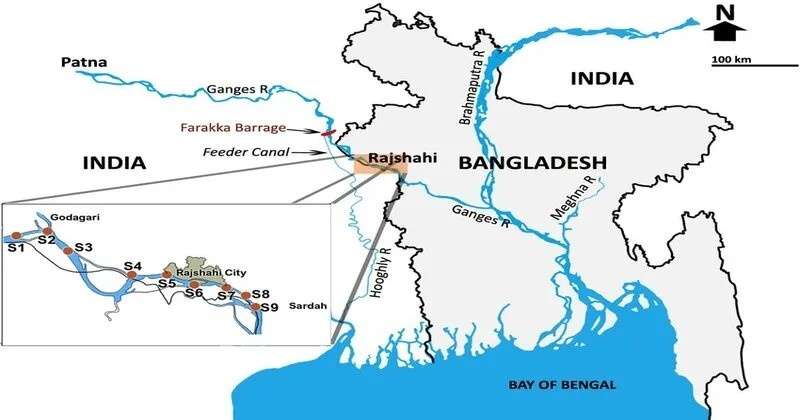

The Ganga Water Treaty of 1996, which controls dry-season flows from the Farakka Barrage, will soon need to be renewed. The treaty allocates water based on a formula: if the river flows under 70,000 cusecs, both countries share equally; between 70,000 and 75,000 cusecs, Bangladesh receives 35,000, while India takes the balance; and, if over 75,000 cusecs, India receives 40,000, while Bangladesh takes the balance.

India’s Strategic Shift: From Indus to Ganges

India is signaling a significant change in its transboundary water diplomacy: having suspended the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan, it is now demanding a renegotiation of the 1996 Ganges Water Sharing Treaty with Bangladesh. Indian officials are arguing that rapid increases in demand for agriculture usage, Kolkata port operations, and demand for hydropower generation have made it necessary to seek a shorter-term agreement (10 or 15 years instead of the original 30-year term) and asking for an additional 30,000 – 35,000 cusecs of water during the critical dry season. Different forms of this recalibration have registered alarm in Dhaka, which sees India’s proposal as not just a response to domestic water turmoil, but also an overarching strategic realignment in the wake of Bangladesh’s pivot to China and recent warming of ties with Pakistan. The optics around India potentially using water-sharing deals like Farakka as a tool of diplomacy in a period of regional turbulence will only increase anxieties.

India-Bangladesh Treaty: Strategic Concerns

The renegotiation of the Ganges Treaty has major implications for millions of people on both sides of the border. In Bangladesh, where agriculture supports around one-third of the workforce and contributes around 11% to GDP, any decrease in dry-season flows has direct implications for food security and rural livelihoods. Crop failures, reduced fisheries, and lack of water for irrigation all threaten the already vulnerable delta areas. Climate change hasn’t helped either; less predictable monsoons and less river flow are increasing stress on rigid, antiquated water-sharing systems. Experts are calling for reforms to treaties to provide minimum guaranteed flows, as well as environmental safeguards along with mechanisms to ensure climate resilience, instead of continuing to utilize historical averages.

At the same time, tensions over other transboundary rivers are unpredictable. Notably, the Teesta River issue cost Bangladesh around 1.5 million tonnes of rice every year, with objections from politicians in West Bengal and Assam’s hydropower project delay continuing to stall resolution. The 2022 Kushiyara deal–entitling Bangladesh to draw 153 cusecs at Rahimpur–shows that functional bilateral regulatory frameworks are possible exploits. However, lurking tensions in the neighborhood lead India to play harder ball. Given more regional implications of water regimes, India’s stronger positions do not reflect just resources but a sense of geostrategic revision in its water diplomacy toolkit to manage.

Geopolitics of the Ganges: India-Bangladesh Perspective

India’s recent efforts to renegotiate the Ganges Treaty coincide with its suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan, demonstrating a significant shift in which transboundary water-sharing has gone from being viewed as a technical, almost non-political issue to one that is functioning as a diplomatic tool of leverage. With this shift, New Delhi is signalling an intention to link water agreements with its actual and emerging national and regional priorities. Central to the tension is the Siliguri Corridor – the narrow, frail “Chicken’s neck” connecting northeast India to the rest of the Indian territory and which runs very close to the Bangladesh, Bangladesh is enhancing its economic as well as strategic relationships with China, meaning that water relations are simultaneously chalking their way into greater regional power dynamics.

The Ganges dispute is no longer simply a technical dispute. It brings together food security, climate policy, regional diplomacy, and strategic positioning. With the 2026 anniversary of the treaty looming, both countries will need to balance their entrenched national interest with a jointly workable sustainable governance model for the river. The decisions taken now will shape not just the Ganges, but the future of South Asia’s environmental and diplomatic landscape