Introduction

India’s latest overhaul of its indirect tax regime through GST 2.0 comes on the heels of recent income-tax rebates that raised effective zero-tax thresholds to nearly Rs.12 lakh, signalling a coordinated effort to boost disposable incomes and household demand. Eight years after the first GST rollout in 2017, the reforms act as both a correction and a catalyst collapsing the old four-tier structure into two principal slabs, while cutting rates on essentials, aspirational goods, healthcare, and insurance. Marketed as a “Bachat Utsav” or savings festival, GST 2.0 seeks to ease the cost of living, energise businesses, and deliver a more predictable and citizen-friendly tax framework.

The timing could not be more critical. With the global economy buffeted by tariff wars, unstable supply chains, and volatile trade rules, India is moving to insulate its growth trajectory by stimulating domestic consumption and strengthening competitiveness. Beyond immediate price relief, GST 2.0 is being positioned as a long-term structural reform that aligns fiscal policy with the vision of Viksit Bharat 2047; a roadmap for a developed, resilient, and globally competitive India capable of withstanding external shocks while ensuring equitable prosperity at home.

A Coordinated Fiscal Strategy: The Link Between Income Tax and GST 2.0

The introduction of GST 2.0 is not an isolated policy event but rather a critical component of a broader, coordinated fiscal strategy aimed at boosting household disposable income and stimulating demand. This approach is anchored by two key measures: the recent income tax rebates and the new GST rates. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman have stated that making income up to Rs.12 lakh tax-free in the Union Budget, combined with the GST rate rationalization, will save citizens over Rs.2.5 lakh crore annually. This deliberate dual approach direct tax relief to increase savings and indirect tax relief to lower spending costs is a powerful tandem designed to inject liquidity directly into the hands of citizens.

This synchronized policy is underpinned by a broader economic philosophy focused on consumption-led growth. Private consumption accounts for 60% of India’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), a far higher share than in many other large economies. By lowering prices on a wide range of goods and services, the government aims to free up household funds that would otherwise be spent on taxes. These freed-up resources are then expected to trigger a multiplier effect, as increased spending fuels demand for goods and services. Higher demand, in turn, is expected to improve industry capacity utilization, thereby incentivizing private businesses to invest in new capital expenditure (capex) in the coming years. This establishes a virtuous cycle of higher demand, better industry performance, and sustained growth, providing a powerful long-term economic narrative. The reforms are strategically timed to coincide with the festive season and are framed as a “Diwali gift” and a “GST Bachat Utsav,” emphasizing a people-centric approach. This symbolic messaging is intended to maximize consumer spending and public goodwill, associating the ruling government directly with tangible financial relief for the common man.

The Genesis and Evolution of GST in India (2000-2017)

To understand GST 2.0, one must first grasp the arduous journey of its predecessor. The introduction of GST in 2017 was the culmination of nearly two decades of political and legislative effort. The concept of a unified indirect tax system was first proposed by the Atal Bihari Vajpayee-led government in the year 2000, and a comprehensive GST model based on the Value Added Tax (VAT) principle was later suggested by the Kelkar Task Force in 2002. The idea’s genesis was to replace a complex, fragmented system of multiple central and state taxes with a single, simplified structure.

The journey was marked by significant legislative milestones. After years of deliberation, the 115th Constitutional Amendment Bill was introduced in 2011 but lapsed. The legislative push was renewed with the introduction of the 122nd Constitutional Amendment Bill in 2014, which was subsequently passed by both the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha in 2016. This bill, upon receiving presidential assent on September 8, 2016, became the Constitution (101st) Amendment Act, 2016. This landmark act conferred simultaneous power upon both the Centre and states to make laws governing goods and services tax, a crucial constitutional shift in India’s federal structure.

Following parliamentary approval, the bill required ratification by at least 15 state legislatures. Assam was the first state to ratify the bill on August 12, 2016, a key political milestone. Jammu and Kashmir was the last state, passing its GST Act on July 7, 2017, just six days after the nationwide rollout, ensuring the entire nation was brought under a unified indirect taxation system. This staggered timeline from first to last state ratification highlights the immense political negotiation and consensus-building required. The 101st Amendment Act also established the GST Council, a constitutional body with the Union Finance Minister and representatives from all states as members. This collaborative governance model became the sole decision-making authority on GST rates, rules, and exemptions, proving essential for the implementation of a unified tax system.

GST 1.0: Achievements and Persistent Challenges

The initial years of GST proved to be a mixed bag of significant achievements and persistent complications. On the one hand, GST was a transformative step in India’s taxation system. It subsumed 17 different taxes and 13 cesses into a single tax, creating “one nation, one tax” and eliminating dozens of state-level checkposts that had long hindered interstate trade. This simplification fostered a single national market and improved the ease of doing business. A significant achievement was the expansion of the tax base, with the number of registered businesses surging from a meager 65 lakh in 2017 to over 1.5 crore by 2025. This formalization contributed to robust revenue growth, as seen in the steady increase in collections. Gross tax collection grew from Rs.7.19 lakh crore in FY 2017-18 to over Rs.22 lakh crore in FY 2024-25, with monthly collections consistently crossing the Rs.1.5 lakh crore mark.

| Financial Year | Total GST Collection (₹ Lakh Crore) | Average Monthly Collection (₹ Crore) |

| 2017-18 | Rs.7.19 Lakh Crore (Jul-Mar) | Rs.89,875 Cr |

| 2018-19 | Rs.11.77 Lakh Crore | Rs.98,083 Cr |

| 2019-20 | Rs.12.22 Lakh Crore | Rs.1.02 Lakh Cr |

| 2020-21 | Rs.11.36 Lakh Crore | Rs.94,667 Cr (COVID Impact) |

| 2021-22 | Rs.14.83 Lakh Crore | Rs.1.24 Lakh Cr |

| 2022-23 | Rs.18.10 Lakh Crore | Rs.1.51 Lakh Cr |

| 2023-24 | Rs.19.80 Lakh Crore | Rs.1.65 Lakh Cr |

| 2024-25 | Rs.22.08 Lakh Crore | Rs.1.84 Lakh Cr |

Table: GST Growth Trend

Despite these successes, GST 1.0 faced persistent complications that hindered its full potential. The multi-tiered structure (0%, 5%, 12%, 18%, 28%) was a major point of criticism, leading to classification disputes and litigation for businesses, especially for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The system’s heavy reliance on the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) also created technological hurdles, with portal failures during rush hours leading to missed filings and fines. The Input Tax Credit (ITC) system, designed to prevent the cascading effect of taxes, also proved problematic, as buyers were often denied credit if their suppliers failed to file correctly, impacting working capital and creating an element of unfairness. Furthermore, the five-year compensation mechanism for states, which was designed to ease their transition, created financial strain and trust issues when delays occurred, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic. The absence of a timely institutional redress mechanism, such as the GST Appellate Tribunal, created a significant backlog of over 40,000 pending cases, adding to the compliance uncertainty for businesses. The robust revenue collection data confirms a fundamental success in formalizing the economy, demonstrating that the system, while complicated, was largely effective in its primary function. The existence of so many unresolved issues, however, created the political and economic imperative for the “next-generation” reforms.

The Imperative for Change: Why GST 2.0 Was Necessary

The shortcomings of GST 1.0, coupled with the need for continued economic momentum, created a compelling case for a major overhaul. The multi-tiered slab system and frequent changes to rules created widespread confusion and a negative public perception of GST as a complex and punitive tax. GST 2.0 was explicitly presented as a solution to this, aiming for simplicity and citizen-centricity by addressing the “Gabbar Singh Tax” criticism head-on. After a dip in collections and economic activity due to the pandemic, the government needed a powerful stimulus. Lowering taxes on everyday essentials and high-value consumer durables was a direct, consumption-driven strategy to revive demand and inject liquidity into the economy.

The reforms are not merely about economic stimulus; they are also a manifestation of a long-term economic and social vision, encapsulated in slogans like “Aatmanirbhar Bharat” and “Viksit Bharat”. By reducing taxes on domestically manufactured goods like small cars and two-wheelers, the government is not just providing a rebate; it is actively supporting domestic manufacturing and making “Made in India” goods more competitive. A key element of this vision is the correction of structural inefficiencies, such as the inverted duty structure in textiles and fertilizers, which led to working capital blockages and litigation. Furthermore, the exemption of health and life insurance premiums is a profound social policy measure aimed at increasing financial security and aligns with the “Mission Insurance for All by 2047” vision. This signals a fundamental shift from treating these as mere taxable services to essential social goods, a crucial indicator of the government’s long-term policy goals.

The Seven Pillars of GST 2.0: A Detailed Breakdown

The Next-Generation GST reforms are anchored around seven core pillars, each crafted to correct structural gaps of GST 1.0 and drive a more citizen-centric, growth-oriented tax regime.

Pillar 1: Building on the Success of GST

Since 2017, GST has unified India’s tax landscape under the “One Nation, One Tax” framework, expanding the taxpayer base and ensuring steady revenues. GST 2.0 consolidates this success with a simplified two-tier structure, making compliance and interpretation easier across states.

Pillar 2: Rationalising Rates for Fairer Taxation

The shift to a 5% and 18% slab system, with a distinct 40% levy on luxury and sin goods, eliminates the earlier complexities of four slabs. This rationalisation reduces classification disputes, smooths duty structures, and ensures faster refunds particularly benefiting sectors prone to inverted duties.

Pillar 3: Simplifying Filing Through Technology

Technology sits at the heart of GST 2.0. Small and low-risk businesses can now secure registration within three days, exporters receive 90% provisional refunds upfront, and end-to-end compliance is powered by e-invoicing and AI-driven risk detection. Together, these measures cut red tape and boost liquidity.

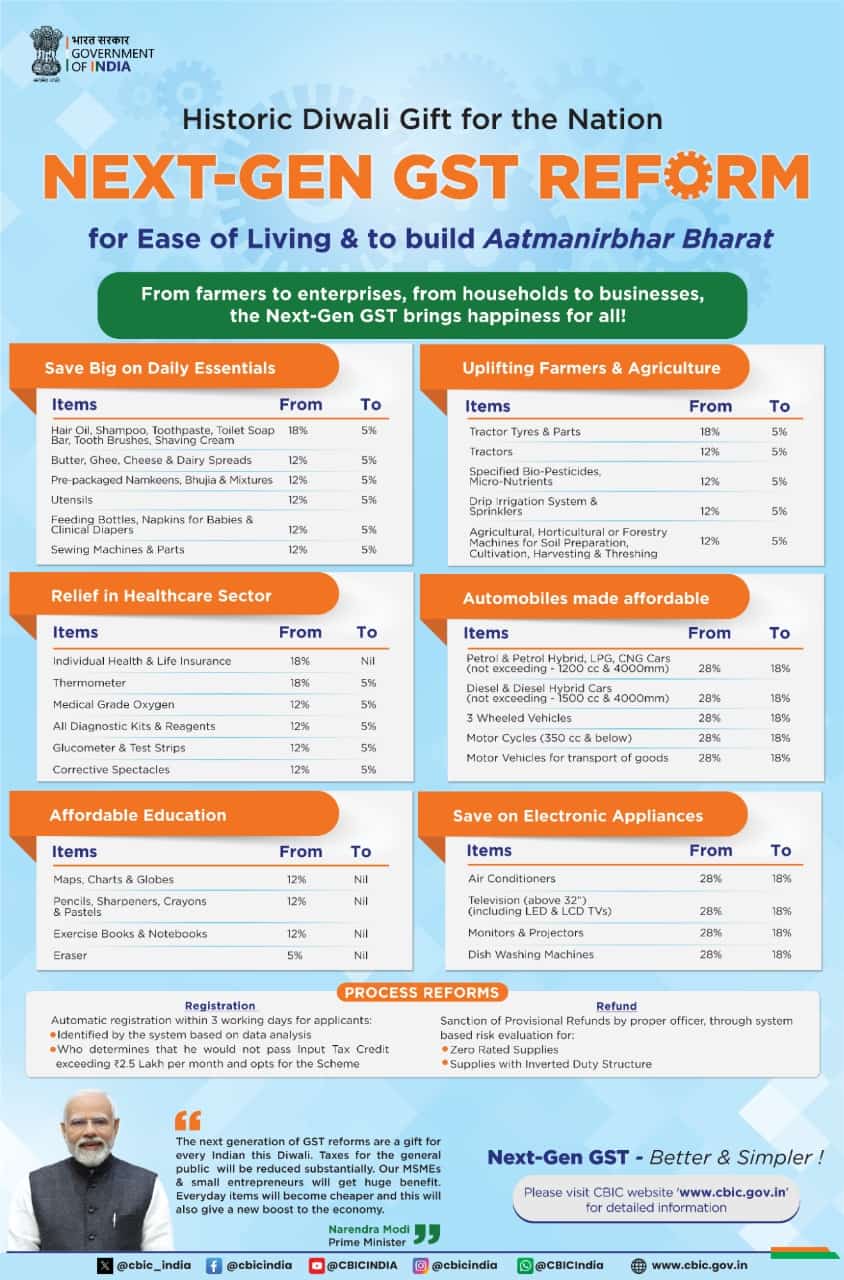

Pillar 4: Keeping Consumers First

The reforms place affordability at the center. Essentials such as food items, soaps, and medicines now fall in the 0-5% bracket, while high-value goods like cars, two-wheelers, TVs, and appliances see reductions from 28% to 18%. This makes daily needs cheaper and aspirations more accessible.

Pillar 5: Empowering MSMEs and Manufacturers

By fixing inverted duty structures, simplifying rates, and ensuring faster refunds, GST 2.0 strengthens cash flows for small businesses and manufacturers. The reforms also align with the Make in India initiative by enhancing competitiveness across domestic and export markets.

Pillar 6: Stronger States, Stronger Bharat

GST 2.0 reaffirms the principle of fiscal federalism. Rationalised rates and rising demand are projected to expand the tax base, delivering sustainable revenue growth for both Centre and States bolstering India’s cooperative federal framework.

Pillar 7: Lower Taxes, Higher Savings

The guiding philosophy is simple: reduced indirect taxes translate into higher disposable incomes. Families save more, demand rises, industries grow, and the economy gains momentum. From cheaper cars and appliances to accessible healthcare and insurance, the multiplier effect of savings is expected to fuel growth across sectors.

PC: PIB

PC: PIB

6. The Impact Analysis: Cheaper, Costlier, and Broader Effects

The GST 2.0 reforms have a tangible and far-reaching impact across various sectors and segments of society.

| Category | Item/Service | Old GST Rate | New GST Rate | Change | Intended

Impact |

| Insurance & Financial Protection | All individual life insurance policies (term, ULIP, endowment) & reinsurance | 18% | NIL | Full exemption | Makes insurance affordable, expands coverage |

| All individual health insurance policies (family floater, senior citizen, reinsurance) | 18% | NIL | Full exemption | Affordable health cover, supports Insurance for All by 2047 | |

| Tax Structure | General GST slabs | 5%, 12%, 18%, 28% | 5%, 18%, special 40% | Simplified structure | Citizen-friendly “Simple Tax,” reduces disputes |

| Daily Essentials & FMCG | Hair oil, soaps, shampoos, toothbrush, toothpaste, bicycles, tableware, kitchenware | 12% / 18% | 5% | Major reduction | Affordable household essentials |

| UHT milk, paneer, Indian breads (roti, paratha, parotta, etc.) | 5% | NIL | Zero-rated | Cheaper daily food basket | |

| Packaged foods: namkeens, bhujia, sauces, pasta, noodles, chocolates, coffee, preserved meat, cornflakes, butter, ghee | 12% / 18% | 5% | Major cut | Boosts demand, lowers food inflation | |

| Consumer Durables | TVs (all sizes), ACs, dishwashers | 28% | 18% | Slab shift | Makes aspirational goods affordable |

| Automobiles | Small cars, motorcycles ≤350cc | 28% | 18% | Slab cut | Benefits middle-class buyers |

| Buses, trucks, ambulances | 28% | 18% | Slab cut | Cheaper logistics & public transport | |

| Three-wheelers | 28% | 18% | Slab cut | Boost for auto industry | |

| Auto parts (all HS codes) | Multiple (12%, 28%) | Uniform 18% | Simplification | Resolves classification disputes | |

| Agriculture | Tractors | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Reduces farming costs |

| Harvesters, threshers, irrigation & poultry/beekeeping machinery | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Encourages mechanisation | |

| Bio-pesticides, natural menthol | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Supports sustainable farming | |

| Construction & Infrastructure | Cement | 28% | 18% | Reduction | Boosts housing & infra |

| Marble, granite, travertine blocks | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Reduces real estate & infra costs | |

| Handicrafts & Labour-Intensive Sectors | Handicrafts, intermediate leather goods | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Protects artisan livelihoods, supports exports |

| Healthcare | 33 lifesaving drugs & medicines | 12% | NIL | Full exemption | Improves access to treatment |

| 3 critical cancer/rare disease drugs | 5% | NIL | Full exemption | Lowers cost of critical care | |

| All other medicines | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Affordable healthcare | |

| Medical apparatus (surgical, dental, veterinary devices) | 18% | 5% | Reduction | Lowers treatment costs | |

| Medical equipment (bandages, kits, glucometers, reagents) | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Affordable diagnostics | |

| Textiles & Fertiliser | Man-made fibre | 18% | 5% | Inverted duty corrected | Boosts domestic textile competitiveness |

| Man-made yarn | 12% | 5% | Inverted duty corrected | Lowers textile costs | |

| Fertiliser inputs (sulphuric acid, nitric acid, ammonia) | 18% | 5% | Inverted duty corrected | Supports fertiliser production, reduces imports | |

| Renewables & Energy | Renewable energy devices & parts | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Promotes clean energy |

| Services (Common Man) | Hotel stays ≤₹7,500/day | 12% | 5% | Reduction | Affordable tourism |

| Gyms, salons, barbers, yoga centres | 18% | 5% | Reduction | Accessible wellness services | |

| Judicial/Institutional | Operationalisation of GSTAT (Goods & Services Tax Appellate Tribunal) | — | — | Functional by Dec 2025 | Streamlines dispute resolution, reduces court load |

Table: What Got Changed in GST-2.0 and its impact

What Got Cheaper?

For the common person, daily essentials like soaps, toothpaste, shampoos, and a wide range of packaged foods have been moved from the 12-18% slabs to the 5% slab. This directly impactsmonthly household budgets. For instance, Amul has reduced prices across 700 products, with ghee becoming cheaper by Rs.40 per litre and Mother Dairy lowering milk prices by Rs.2 per litre.

For the middle class, high-ticket consumer durables, including ACs, TVs over 32 inches, and dishwashers, have been moved from the 28% to the 18% slab, making aspirational purchases more affordable. Similarly, the GST on small cars and two-wheelers up to 350cc has been reduced from 28% to 18%, translating into savings of thousands of rupees for consumers.

Farmers are among the biggest beneficiaries, with taxes on farm machinery, tractors, irrigation equipment, and fertilizers slashed from 12-18% to 5%. This is expected to reduce farming costs by up to 13% and even help with environmental issues like stubble burning by making modern equipment like straw reapers more affordable for small farmers.

The youth and salaried class will see significant relief through GST exemptions on life and health insurance premiums, which will save them thousands of rupees annually and encourage better financial planning. The reduction in GST on services like hotel stays (up to Rs.7,500/day), gyms, and salons from 18% to 5% makes wellness and leisure more accessible and supports domestic tourism.

| Item/Sector | Old GST Rate (%) | New GST Rate (%) | Notes on Impact |

| Cement | 28 | 18 | Lowers home and infrastructure costs, boosts real estate demand. |

| Small Cars (petrol ≤ 1200cc) | 28 | 18 | Reduces cost for middle-class families, supports domestic manufacturing. |

| Two-wheelers (≤ 350cc) | 28 | 18 | Reduces cost for daily commuters and boosts sales. |

| ACs, TVs (≤ 32 inches) | 28 | 18 | Makes consumer durables more affordable, supporting domestic manufacturing. |

| Farm Machinery/Tractors | 12 | 5 | Reduces costs for farmers, promotes modern and sustainable agriculture. |

| Life/Health Insurance Premiums | 18 | 0 | Increases financial protection, supports ‘Insurance for All’ vision. |

| Household Essentials (soaps, toothpaste) | 18 | 5 | Direct relief on daily expenses, boosts household savings. |

| Packaged Foods (biscuits, sauces) | 12-18 | 5 | Reduces monthly grocery bills for households. |

| Medical Devices & Drugs | 12-18 | 5 or 0 | Improves access to healthcare, supports domestic pharma manufacturing. |

What Got Costlier?

The new 40% tax slab is exclusively for a limited set of luxury and “sin goods”. This includes products like cigarettes, pan masala, gutkha, certain high-end cars and motorcycles with engine capacity over 350cc, aerated drinks, and gambling/betting services. This “more income, more tax” approach on these items is a clear policy signal designed to ensure fairness and maintain government revenue. Additionally, some discretionary items, like clothes priced above Rs.2,500, now attract an 18% GST compared to the earlier 12%.

| Item | Old GST Rate (%) | New GST Rate (%) | Notes on Impact |

| Pan Masala, Cigarettes, Tobacco Products | 28 + Cess | 40 | Taxes are intended to deter consumption of demerit goods. |

| Luxury Cars (> 1200cc petrol, > 1500cc diesel) | 28 + Cess | 40 | Higher tax on high-end automobiles to maintain revenue and social equity. |

| Motorcycles (> 350cc engine capacity) | 28 + Cess | 40 | Imposed higher tax on luxury two-wheelers. |

| Aerated & Sugary Drinks | 28 | 40 | Increased tax on beverages containing added sugar or flavoring. |

| Yachts & Private Aircraft | Not specified | 40 | Higher taxes on luxury purchases. |

| Betting, Gambling, Casinos, Horse Racing | Not specified | 40 | New tax on actionable claims, a major change. |

The exemption of GST on life insurance and health premiums is not just a financial cut; it is a policy tool for social engineering. The government is using the tax system to actively incentivize behavior that aligns with its broader social and economic goals. Historically, low insurance penetration was partly due to high costs. By making health and life insurance more affordable, the government is transforming it from a luxury into a more accessible necessity. This not only increases financial protection for citizens but also reduces the long-term burden on public healthcare systems. Similarly, the reduced tax on farm machinery is a direct policy intervention to encourage modern agricultural practices and address the public health crisis of air pollution caused by stubble burning.

Political and Critical Discussion

The implementation of GST 2.0 is an economic reform, but its timing and messaging make it a significant political event. The term “masterstroke” is applicable due to the strategic timing and framing of the reforms. Launching the reforms just before the festive season and associating them with a “GST Bachat Utsav” is a highly effective political move. It directly counters the historical “Gabbar Singh Tax” criticism by positioning the government as a benefactor to the common person. The messaging, led by the Prime Minister and Home Minister, is focused on the direct, tangible benefits to “the poor, youth, farmers, and women”.

Despite the political narrative, the reforms address long-standing, well-documented challenges of GST 1.0. The simplification of tax slabs, the correction of inverted duty structures, and the focus on easing compliance for MSMEs are substantive and long-overdue policy changes. These structural reforms are not merely cosmetic; they are expected to have a lasting positive impact on the economy by improving competitiveness and efficiency. The shift of most items to the 18% slab and the existence of a high 40% slab indicate a genuine attempt to create a more efficient and rationalized system.

The GST Council’s role in this process is particularly noteworthy. As a consensus-based body where states hold two-thirds voting weight, any major policy change requires careful negotiation. The states’ caution regarding any changes that could lead to revenue shortfalls has historically been a barrier to major reforms. The successful implementation of these sweeping rate reductions and structural changes implies a renewed or reinforced political consensus within the Council. While there may be short-term fiscal pressure for some states, the long-term promise of a larger tax base and increased economic activity has likely secured their buy-in. This indicates a maturing of the GST federal governance model, demonstrating a capacity for large-scale, collaborative policymaking. Thus, GST 2.0 is both a political masterstroke and a genuine, necessary reform.

Why GST 2.0 Matters

GST 2.0, then, is more than a fiscal reset; it is a statement of intent. By coupling tax relief with structural simplification, the reforms lay the groundwork for a transparent and citizen-centric regime that strengthens India’s case as a resilient economy on the road to Viksit Bharat 2047. If implemented with rigour, the new framework will not only widen compliance and formalisation at home but also fortify India against external tariff headwinds in an increasingly protectionist world. The measure of success will lie less in the celebratory rhetoric of a “savings festival” and more in the long-term stability, equity, and competitiveness it delivers to India’s economic journey.