China is taking another attention focuses on flashpoints like Taiwan and the South China Sea, China has been quietly perfecting the art of territorial conquest in one of the world’s most peaceful kingdoms. Bhutan, the tiny Himalayan nation famous for measuring Gross National Happiness instead of GDP, is discovering that happiness offers little protection against a neighbors calculated aggression.

What’s happening in Bhutan is not just another border dispute it’s a masterclass in what military strategists call “salami slicing,” the practice of taking territory bit by bit, so gradually that the victim barely notices until it’s too late. The Chinese approach is methodical, almost surgical in its precision, and devastatingly effective.

The Seven-Step Recipe for Conquest

The Chinese playbook for territorial expansion follows a predictable pattern that has been refined over decades. It begins innocuously enough as herders and grazers are sent into disputed areas, appearing to simply tend their animals. These aren’t random pastoral movements; they’re carefully orchestrated probes designed to establish the first foothold of Chinese presence.

Once the herders are established, the next phase begins. Temporary shelters appear, ostensibly to protect these “innocent” civilians from harsh mountain weather. Military patrols soon follow, justified as necessary protection for Chinese citizens in remote areas. These patrols then require their own infrastructure or should say outposts, communication equipment, and permanent structures that transform temporary presence into lasting occupation.

The fourth step involves connecting these outposts to the broader Chinese infrastructure network. Roads are built from Tibetan towns, creating permanent supply lines that make retreat practically impossible. This is exactly what happened in 2017 at Doka La, when Chinese road construction triggered a tense 73-day standoff with Indian forces.

The final phases complete the transformation from occupation to integration. Border settlement villages are established, 22 of them have sprouted in the Doka Lam area alone since the 2017 standoff. Tourism is then promoted to normalize the occupation, creating a veneer of legitimate development over what amounts to territorial theft.

Bhutan’s Disappearing Territory

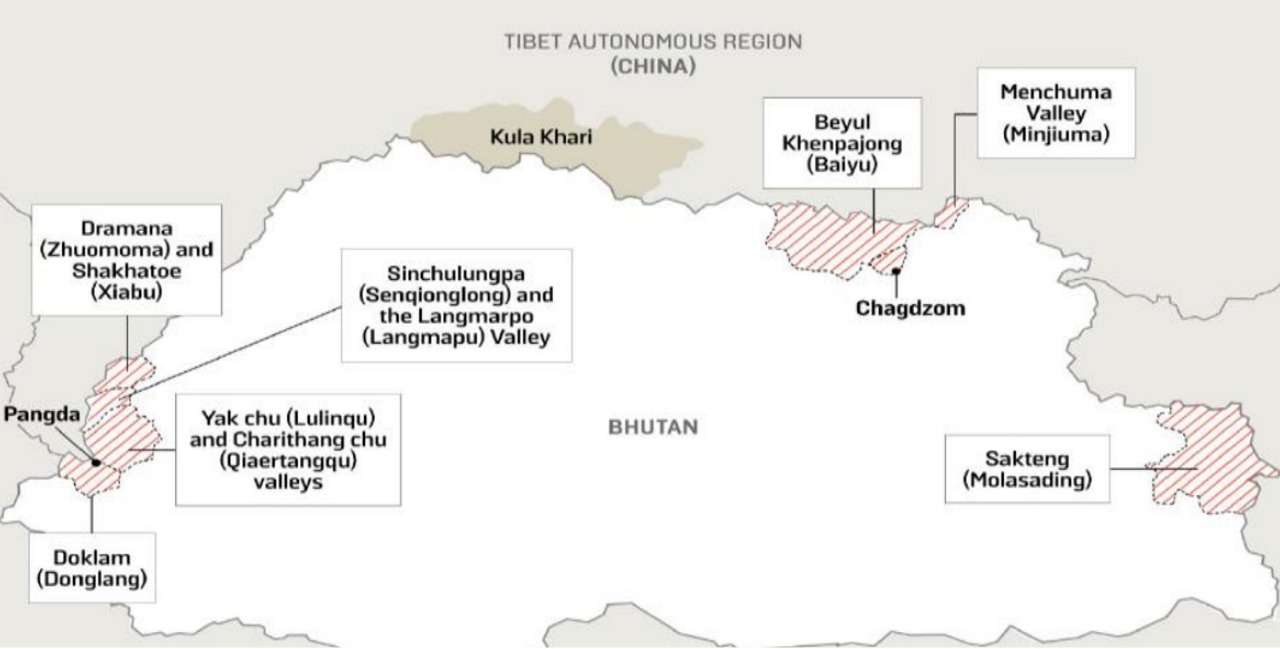

The scale of Chinese encroachment in Bhutan is staggering. Nineteen villages and three settlements have been established in territory that Bhutan considers its own. Eight of these villages occupy the Doka La region in western Bhutan, covering four and a half of the seven valleys along the tributaries of the Amu Chu river. Another fourteen villages have appeared in northeastern Bhutan, areas that had never seen permanent Chinese settlement before.

This isn’t accidental sprawl it’s strategic positioning. The Chinese are systematically occupying key valleys and chokepoints that could control Bhutan’s access to its own territory. Each village represents not just a few dozen buildings, but a permanent alteration of the demographic and political landscape.

The psychological impact on Bhutanese communities cannot be overstated. Imagine waking up to find foreign settlements in valleys your ancestors considered sacred, roads cutting through pristine wilderness, and military patrols in areas where your grandparents once grazed yaks in peace.

The Tibet Connection

Understanding China’s actions in Bhutan requires recognizing the historical context that drives Beijing’s territorial ambitions. Every Chinese claim along the Bhutan-Tibet border ultimately rests on China’s 1951 occupation of Tibet, a formerly independent nation that had maintained its sovereignty for centuries.

This creates a cruel irony: China is using its occupation of one previously independent nation to justify the gradual absorption of another. The Tibetan plateau, once a buffer between China and the Indian subcontinent, has become a launching pad for further expansion.

The forced urbanization of Tibetan nomads which were justified as poverty elimination—serves dual purposes. It disrupts traditional Tibetan culture while creating demographic pressure that pushes Chinese settlers into previously uninhabited border areas. These displaced populations become unwitting pawns in China’s territorial chess game.

The Chumbi Valley Gambit

Perhaps the most audacious aspect of China’s Bhutan strategy involves the Chumbi Valley, a narrow finger of Chinese territory that juts between India and Bhutan like a dagger pointed at the heart of the Indian subcontinent. This valley, barely 50 kilometers long and 20 kilometers wide, represents one of China’s most significant strategic vulnerabilities.

The Chinese solution is characteristically bold: convince Bhutan to resolve all border disputes through a package deal that would legitimize Chinese control over central Bhutan territories in exchange for Chinese withdrawal from western areas. This would effectively eliminate China’s Chumbi Valley vulnerability while giving Beijing control over strategically vital areas deeper in Bhutan.

The genius of this approach lies in its apparent reasonableness. To outside observers, it looks like a fair trade—each side gives up something to gain something else. In reality, it would formalise Chinese control over territory that was never legitimately theirs while creating new strategic advantages for future expansion.

Digital Dominance and Infrastructure Control

China’s territorial ambitions extend beyond physical occupation to complete technological control. Under the guise of digitization and development, the People’s Liberation Army has extended 5G and fiber optic networks to 70% of border villages, with 4G coverage reaching 90% of these settlements.

This isn’t just about providing internet access to remote communities. It’s about creating a comprehensive surveillance and control network that makes Chinese occupation irreversible. Every smartphone, every communication device, every digital transaction becomes part of a vast intelligence network that monitors and controls the occupied territories.

The construction of airports compounds this advantage. Of the 35 airports planned for Tibet, one is specifically located in Yadong, directly adjacent to Bhutan. This transforms what was once a remote mountain region into a rapidly accessible strategic outpost, capable of receiving reinforcements and supplies within hours rather than days.

The Diplomatic Trap

China’s ultimate goal appears to be the establishment of a Chinese embassy in Thimphu, Bhutan’s capital. This would represent the final step in legitimizing Chinese influence over Bhutan, transforming the kingdom from India’s close ally into a neutral buffer state at best, or a Chinese client state at worst.

The brilliance of China’s approach lies in its exploitation of Bhutan’s traditional governance style. The kingdom’s rulers, accustomed to resolving disputes through patient dialogue and consensus-building, find themselves outmaneuvered by an adversary that uses negotiations as cover for continued expansion.

Even the 2020 Chinese claim over the Sakteng area in eastern Bhutan, a region that doesn’t even share a border with Tibet, demonstrates the escalating audacity of Chinese territorial demands. This artificial claim, never before asserted by any Chinese government, illustrates how Beijing’s appetite for Bhutanese territory continues to grow.

The Regional Implications

China’s strategy in Bhutan has implications far beyond the kingdom’s borders. The 300-plus obsolete T-59 tanks gifted to Bangladesh in 2017 weren’t acts of generosity—they were strategic investments designed to create additional pressure on India from the east while China consolidated its position in the north.

The militarization of the Chumbi Valley, including the deployment of PHL03 multiple launch rocket systems for “training purposes,” transforms what was once a geographic curiosity into a genuine military threat. These weapons systems can reach deep into Indian territory, turning a narrow valley into a strategic springboard for potential conflict.

The Broader Pattern

What’s happening in Bhutan represents more than a bilateral dispute—it’s a preview of China’s approach to territorial expansion in the 21st century. The salami-slicing technique, refined through decades of practice in the South China Sea and along the India-China border, has found its perfect testing ground in the peaceful valleys of Bhutan.

The kingdom’s commitment to Gross National Happiness, its Buddhist traditions of non-violence, and its preference for quiet diplomacy over public confrontation make it an ideal target for gradual conquest. Each Chinese advance is small enough to avoid triggering major international attention, yet collectively they represent a fundamental alteration of regional power dynamics.

The January 2022 implementation of China’s new Border Law, which legalizes and streamlines administration of occupied areas, suggests that Beijing considers its Bhutanese territories permanently integrated into Chinese administrative structures. This isn’t temporary occupation—it’s permanent annexation disguised as development.

The Future of the Last Shangri-La

Bhutan’s tragedy lies in its virtues. The kingdom’s peaceful nature, its respect for traditional ways of life, and its commitment to environmental preservation make it a treasure worth protecting. But these same qualities leave it vulnerable to a neighbor that views such virtues as weaknesses to be exploited.

The Chinese campaign for the “Sinicization of Buddhism” adds cultural imperialism to territorial conquest. By attempting to reshape Bhutanese religious practices to align with Chinese interpretations, Beijing seeks to undermine the spiritual foundations of Bhutanese identity itself.

As the world watches dramatic confrontations unfold in more visible theaters, the quiet conquest of Bhutan continues. Each new village built, each new road constructed, each new patrol established represents another step toward the disappearance of one of the world’s most unique nations.

The question isn’t whether China will continue its expansion into Bhutan—the pattern is too well-established and the strategic benefits too significant for Beijing to abandon its approach. The question is whether the international community will recognize what’s happening before it’s too late, or whether the world will wake up one day to discover that the last Shangri-La has quietly disappeared behind the Great Wall.