Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s September 2025 visit to China, after a gap of seven years, has been widely described as a watershed in India’s foreign policy. It occurred in a moment of intense flux in the global order: Donald Trump’s tariff shocks had unsettled global trade, Russia was seeking to consolidate its position amidst prolonged Western sanctions, and China was grappling with a slowing economy alongside its rivalry with Washington. Against this backdrop, Modi’s decision to personally attend the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Beijing carried symbolism that far exceeded the mechanics of multilateral diplomacy. It was at once a signal of India’s intent to recalibrate equations with China, a reaffirmation of its reliance on Russian energy security, and a reminder to the United States that India will not be taken for granted as a junior partner.

U.S. Tariff Shock and India’s Economic Vulnerability

The immediate trigger for this recalibration was the tariff spiral unleashed by the Trump administration. On 2 April 2025, the United States announced reciprocal tariffs of 25 percent on imports from nearly one hundred countries, India included. The decision came into force in early August, instantly disrupting Indian exports in sectors such as textiles, pharmaceuticals, and IT hardware. Given that merchandise exports contribute around 21 percent of India’s GDP, the shock was significant. Matters worsened when, on 27 August, Washington imposed an additional 25 percent “penalty tariff” on crude supplies linked to Russian imports that were being processed in India. Industry estimates suggested that these twin measures could cost India between $12 and $15 billion annually. The government’s response was not to retaliate with counter-tariffs but to accelerate a shift toward alternative trading systems. By mid-2025, over 90 percent of India-Russia crude trade was being conducted in rupees and rubles, while India and the UAE had operationalised rupee-dirham settlement mechanisms. These moves coincided with BRICS discussions on a non-dollar clearing system, which India cautiously supported, though with reservations about China’s disproportionate role in such an arrangement.

The Russia Factor: Energy Ties in a Strategic Context

The Russia Factor: Energy Ties in a Strategic Context

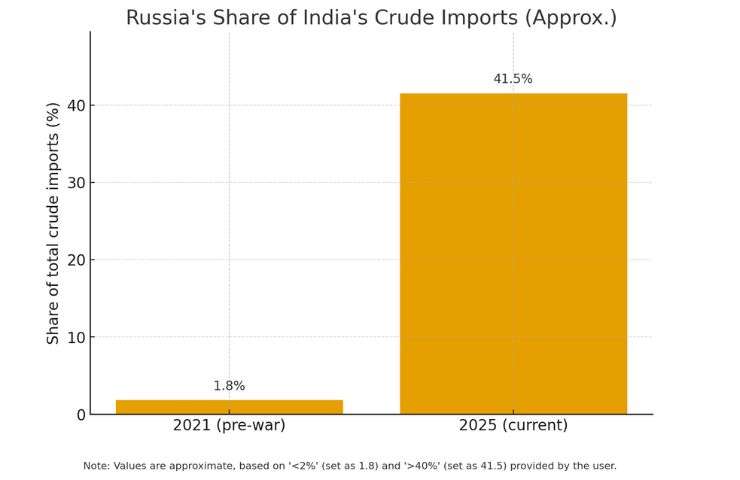

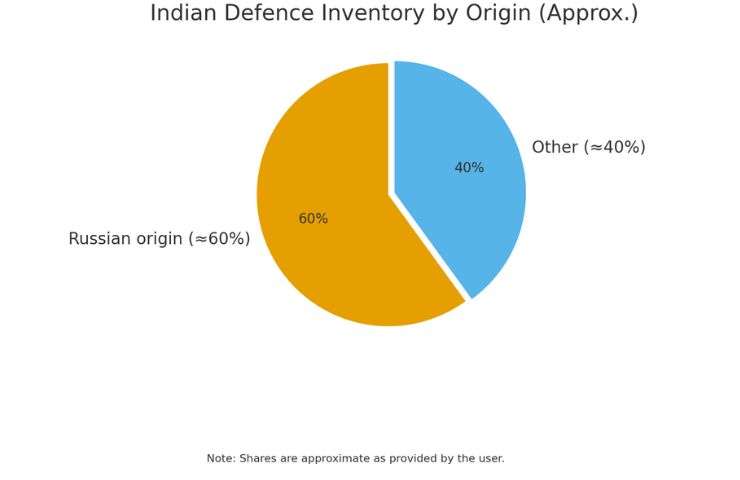

The Russia factor remains central to this calculus. Moscow has become India’s largest crude supplier, accounting for more than 40 percent of total imports compared to less than 2 percent before the Ukraine war in 2021. Russian crude, often discounted at $8-10 per barrel, has been instrumental in keeping Indian inflation within the Reserve Bank of India’s 4-6 percent target band despite global volatility. Beyond energy, Russia continues to be indispensable to India’s defence architecture, with nearly 60 percent of military inventory still of Russian origin. Modi’s bilateral with President Putin on the sidelines of the SCO focused on streamlining rupee-ruble payments, securing uninterrupted supplies of spare parts for Russian platforms in Indian service, and exploring joint ventures in hydrocarbons such as Sakhalin-1 and Arctic LNG projects. For Moscow, which faces exclusion from Western financial systems, Delhi’s engagement is not merely symbolic but a lifeline that reinforces its strategic pivot to the East.

The China Equation: From Hostility to “New Normal”

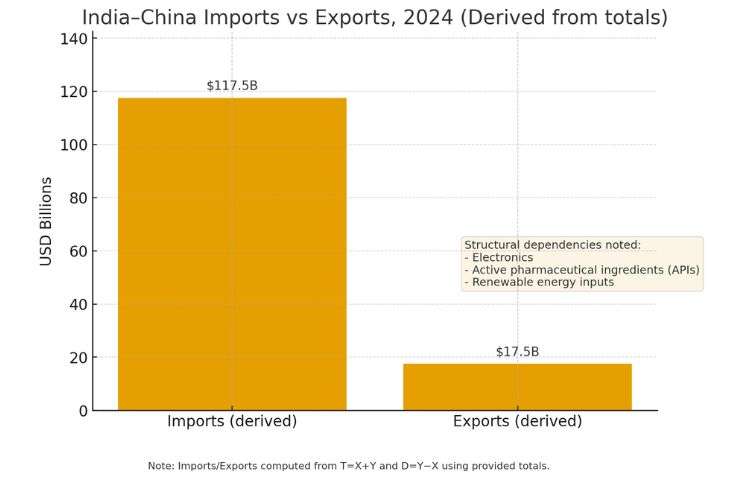

China presents a more complex equation. Bilateral trade touched $135 billion in 2024, making Beijing India’s largest trading partner, yet the trade deficit stood at an unprecedented $100 billion. The dependency is structural, spanning electronics, active pharmaceutical ingredients, and renewable energy inputs. Politically, the relationship has been frozen since the Galwan clash of 2020, and trust remains low. Yet the Modi-Xi meeting signalled an attempt to create a “new normal” of compartmentalisation. The leaders agreed to revive the 2013 Border Defence Cooperation Mechanism, which had lapsed in the aftermath of the clashes, and discussed modest steps toward market access for Indian IT services in China. Xi framed his appeal in civilisational terms, calling for “Asian unity against external tariffs” in a clear allusion to Trump’s trade war. Modi, however, maintained a careful balance, emphasising dialogue and sovereignty without aligning India explicitly with Beijing. This duality underscores India’s strategy: stabilise disputes to prevent escalation, while leveraging economic ties for national interest, but without crossing the threshold into strategic dependence.

Pakistan and the Regional Undercurrent

Pakistan, though present at the SCO through Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, was kept deliberately peripheral to India’s engagements. No bilateral meeting took place, and Modi limited his references to terrorism emanating from Pakistani soil. Trump’s repeated claims of mediating the India-Pakistan ceasefire were dismissed outright by Delhi, which has consistently rejected third-party involvement. The optics of Modi interacting closely with Putin and Xi while ignoring Islamabad were intentional, underscoring that India now sees its geopolitical stage as Eurasian and Indo-Pacific, not confined to South Asia’s binary rivalries.

SCO and BRICS: India’s Leadership Calculus

India’s activism at SCO and BRICS also deserves attention. At the SCO, Modi emphasised three domains: counter-terrorism, where India proposed a joint database of extremist organisations; connectivity, where he reiterated opposition to projects crossing Pakistan-occupied Kashmir; and digital public goods, where India pushed for the creation of a Digital Inclusion Fund inspired by its domestic digital stack. At BRICS, Delhi walked a tightrope. On one hand, it acknowledged the trend toward de-dollarisation; with Russia and China already conducting 90 percent of their bilateral trade in rubles and yuan, and Russia and Iran transacting 95 percent in rubles and rials. On the other hand, it resisted calls for a single BRICS currency, fearing it would consolidate China’s dominance. Instead, India promoted a multi-currency clearing platform and positioned its Unified Payments Interface as a model for cross-border adoption in the Global South.

The Trump-Xi-Putin Triangle: India’s Calculated Position

The triangular interplay with Trump, Putin, and Xi further highlights India’s calculated positioning. Trump has oscillated between threats of 100 percent tariffs on China, outreach to Putin in Alaska, and punitive measures against India. Putin has consistently framed Eurasia as a zone of historic unity, seeking to align Russia with both India and China to offset Western sanctions. Xi has attempted to project SCO as an Asian alternative to Western alliances. Modi’s rhetoric, however, remained restrained. By invoking sovereignty, equality, and dialogue, he neither endorsed anti-U.S. postures nor alienated his Western partnerships. This balance is the essence of India’s strategic autonomy; a determination to engage all sides without being locked into any bloc.

Outcomes of Modi’s Visit

The immediate outcomes of Modi’s visit may appear modest but carry long-term significance. The resumption of structured dialogue with Xi after years of freeze reduces the risk of accidental escalations along the Line of Actual Control. Agreements with Russia on smoother financial settlements secure India’s energy lifeline at a time of global uncertainty. The Digital Inclusion Fund proposal positioned India as a technological leader within SCO, reinforcing its credentials as a provider of low-cost, scalable solutions to the Global South. Above all, the optics of Modi, Putin, and Xi together projected the image of a multipolar order challenging the narrative of U.S. unilateral dominance.

Constraints and Strategic Realities

Yet structural constraints remain. India’s membership in the QUAD inherently ties it to Indo-Pacific balancing against China. The LAC dispute is far from resolved, and the legacy of Galwan continues to cast a shadow. India rejects China’s Belt and Road Initiative, a centrepiece of Beijing’s Eurasian strategy. Russia remains entangled in Ukraine, while China focuses on Taiwan, leaving little space for coherent joint planning. Unlike NATO, neither SCO nor BRICS offers collective security guarantees, unified command structures, or binding military commitments. What we are witnessing is strategic signalling, not structural transformation.

Policy Recommendations for India

The policy implications for India are clear. It must continue to diversify its trade partners through free trade agreements with the European Union, ASEAN, and the Gulf states, thereby mitigating tariff vulnerability. It should cautiously engage China by restoring confidence-building measures and expanding selective economic cooperation without compromising territorial claims. Russia will remain critical for energy and defence, but over-dependence must be avoided through diversification into Middle Eastern and U.S. supplies alongside domestic renewable expansion. Finally, India must actively shape the financial architecture of BRICS, promoting a multi-currency system that avoids yuan dominance and leveraging its fintech capabilities as a counterweight.

Conclusion: Optics with Substance or Strategic Mirage?

In conclusion, Modi’s visit to China did not herald the birth of a new alliance, nor did it resolve the underlying disputes with Beijing. Its significance lies in the optics of multipolarity and the assertion of India’s role as a pivotal swing state. By standing alongside Putin and Xi, Modi reminded Washington that punitive tariffs could push Delhi into broader Eurasian dialogues. By engaging China, he reduced risks of escalation while preserving room for manoeuvre. By deepening ties with Russia, he secured short-term energy stability amidst sanctions. What emerges is not alignment but agency: India’s foreign policy is now less about choosing between East and West, and more about extracting value from all sides while defending strategic autonomy. In an era defined by tariffs, sanctions, and shifting alliances, India’s ability to sustain this flexibility will determine whether its multipolar diplomacy translates into tangible economic and security gains.