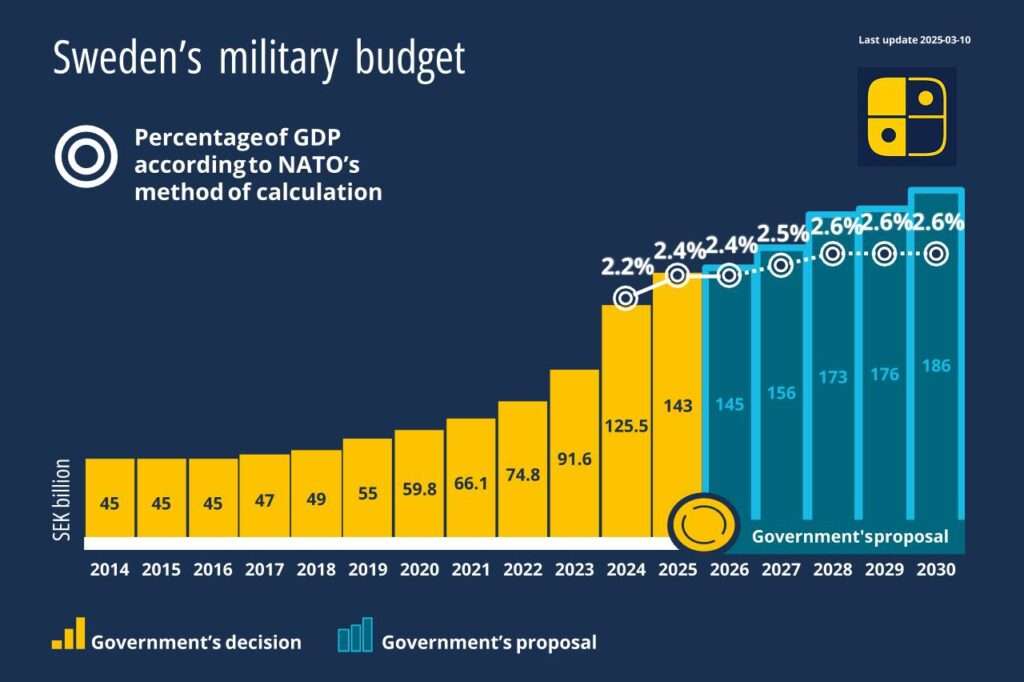

Sweden has recently announced a just under $85 billion budget proposal ahead of elections; it would combine internal relief with a considerable boost in military spending. The government indicated there would be tax cuts for workers and pensioners, cuts on the VAT for food, budget assistance for household to help with living cost. The most striking aspect is the massive increase in defence spending; it will amount to 2.8% of GDP in 2026 and will target 3.5% by 2030.

Much of the budget points to a major change in the defence posture of Sweden. After decades of military non-alignment, Sweden’s accession to NATO in 2023 has caused Stockholm to make a meaningful commitment of resources to collective defence. Sweden’s new spending will modernise air defence systems, increase rocket artillery, naval capacity, and troop readiness. Thus, the message is clear: deterrence. Sweden will not simply remain a state which simply coexists with a regional security architecture, but intends to be a credible contributor to regional security, especially in the Baltic and Arctic, where Russia’s resurgence has always been the primary issue.

For allies, the move signals reliability: Sweden is not just joining NATO on paper but bearing the financial and strategic burdens. For adversaries, it marks a warning that Sweden’s security will no longer be a soft flank. Domestically, the government is also using security and tax relief to appeal to voters, blending national defence with pocketbook issues in a classic election strategy.

Sweden’s decision reflects a broader European trend of rearmament since the Ukraine war. With low national debt, Stockholm can afford to expand defence while stimulating the economy. Yet the long-term challenge will be balancing high military commitments with economic resilience in an uncertain global landscape.