Introduction: War in the Digital Age

Warfare is no longer just about tanks, soldiers, and borders. The traditional image of battlefields has been replaced by something far more complex and far more dangerous. In today’s hyper-connected world, smartphones, drones, and social media platforms have become as critical to modern conflict as missiles and rifles.

This is evident in conflicts like the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, where civilians play an active role by using apps to report troop movements. Urban warfare now involves not only UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) and high-resolution satellite images but also encrypted communication systems, acoustic sensors, and an invisible weapon that operates 24/7 and that is information.

India experienced the sharp edge of this new form of conflict in 2020, during the Galwan Valley clash with China. Alongside the physical confrontation, India found itself under siege in the digital domain, facing cyberattacks and psychological operations orchestrated by the Chinese state machinery.

This article examines how China has weaponized information as part of its broader warfare strategy, focusing on its actions against India, especially during the Galwan Valley crisis. We will also look at the wider pattern of Chinese cyber aggression from 2020 to 2025.

China’s Grey Zone Warfare: Beyond Bullets

China’s military doctrine has evolved dramatically since it observed the U.S. dominance in the 1991 Gulf War. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) realized that information superiority could be as decisive as military firepower. This led to the development of strategies that integrate:

These tactics fall under what experts call grey zone warfare—actions that don’t cross the threshold into open armed conflict but are more aggressive than normal diplomatic or economic competition.

At the heart of China’s strategy is informatized warfare—a method of controlling information flows to disrupt an enemy’s decision-making. This includes hacking into military networks, disabling satellites, jamming communications, and flooding social media with propaganda.

The Galwan Valley Clash: A Case Study in Digital Manipulation

During the 2020 Galwan Valley clash, China didn’t just send troops—it launched an information war. Between June 15 and June 30, 2020, over 40,000 cyberattacks targeted Indian systems, ranging from critical infrastructure to private sector networks.

Alongside cyber intrusions, a coordinated disinformation campaign unfolded:

Key Tactics Used by China

- Fake Combat Videos – A video surfaced on YouTube and X (formerly Twitter), purporting to show Indian and Chinese soldiers in combat. It turned out to be old footage, recycled from previous years.

- Emotional Manipulation – An emotional video was trending on social media, showing Indian soldiers in tears, embracing one another, while others carry what seems to be a body bag.

3. A video shared on Twitter, capturing a heated exchange between Chinese and Indian soldiers, has garnered thousands of views.

3. A video shared on Twitter, capturing a heated exchange between Chinese and Indian soldiers, has garnered thousands of views.

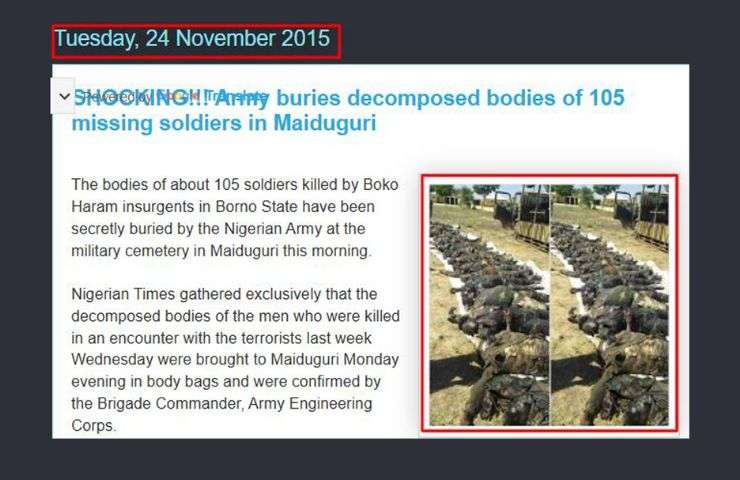

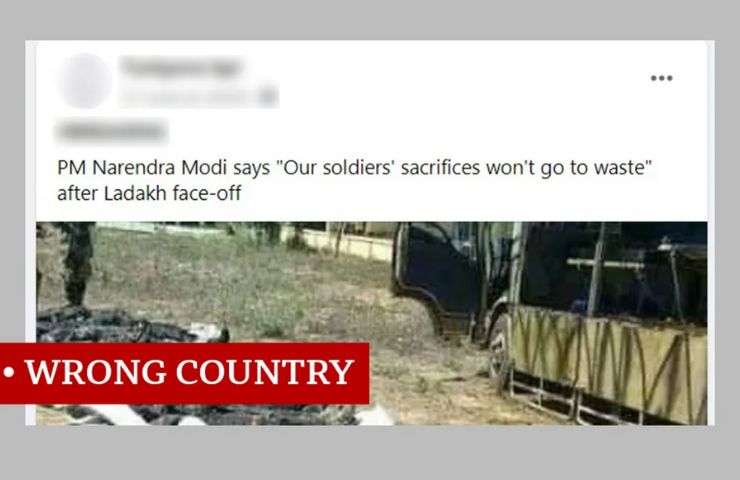

4. Doctored Images of Casualties – A Chinese-language article about the India-China clash features images that allegedly show the bodies of Indian soldiers killed in the confrontation. That article had more than 100,000 views, and one of its image was also appeared on the Pakistani news outlet Baaghitv.

4. Doctored Images of Casualties – A Chinese-language article about the India-China clash features images that allegedly show the bodies of Indian soldiers killed in the confrontation. That article had more than 100,000 views, and one of its image was also appeared on the Pakistani news outlet Baaghitv.

A quick reverse image search reveals that the photo is actually from Nigeria. It shows the aftermath of a 2015 attack in which Nigerian soldiers were killed by Boko Haram militants.

Operation Sindoor: A Battle to Change Perceptions

Following the terror attack in Pahalgam, Operation Sindoor sparked a digital war across social media platforms, drawing India, Pakistan, and China into a fierce battle of narratives. Propaganda and misinformation spread rapidly, with fake videos where some falsely showing Israeli airstrikes and explosions were being shared as so-called proof of Indian or Pakistani military actions.

China and Pakistan appeared to support each other’s versions of events, with Chinese media even alleging that Pakistani forces had downed Indian fighter jets. In response, India briefed international diplomats and released footage to back its claims.

Here are some instances where Chinese media outlets shared some misinformation –

- On 7th May 2025, Indian embassy in China, asked Global Times in a post on X, to verify the news before posting on its platform –

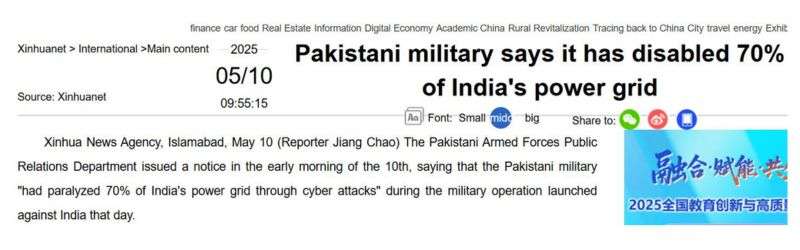

2. On May 10, Xinhua reported that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Public Relations claimed Pakistani cyberattacks had knocked out 70 percent of India’s power grid during Operation Bunyan Marsoos.

2. On May 10, Xinhua reported that Pakistan’s Inter-Services Public Relations claimed Pakistani cyberattacks had knocked out 70 percent of India’s power grid during Operation Bunyan Marsoos.

3. Another outlet, China.com reported that Pakistan had destroyed a BrahMos missile storage site in India which was firmly dismissed as false and misleading by Indian government.

4. Pakistan’s allegation that India attacked the Neelum-Jhelum hydropower station was being circulated by Chinese media outlets such as Sina News. This accusation was denied by India’s Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri.

Biased Narratives and Misleading Terminology

Many reports covering the India-Pakistan conflict have framed events in a way that deflects criticism from Pakistan, particularly regarding its alleged support for state-sponsored terrorism.

An article by Xinhua, mirroring the tone of most Chinese state-run media which refers to the Pahalgam terrorist attack simply as a “shooting incident,” minimizing the severity of the assault.

Even Baidu Encyclopedia’s entry on the India-Pakistan conflict, which provides a detailed overview of bilateral tensions, uses the same term, seemingly portraying India’s military response as excessive or unjustified.

This pattern of downplaying or omitting key details has been echoed by Chinese scholars and analysts.

Lin Minwang, a professor and director at Fudan University’s Institute of South Asia Studies, wrote in a QQ News piece that blaming Pakistan for violence in Indian-administered Kashmir reflects Indian speculation rather than fact.

He argues that such accusations obscure the deeper roots of the Kashmir conflict and render India’s military action against Pakistan illegitimate.

Similarly, Liu Zongyi has suggested that the Modi government’s emphasis on Pakistan’s role is a political tactic to distract from domestic shortcomings.

By glossing over the context leading up to the escalation and underreporting the nature of the terrorist attack, much of the Chinese media narrative implies that India’s retaliation was unprovoked. Even the Chinese Foreign Ministry’s statement condemning “all forms of terrorism” appears to place India and Pakistan on equal footing—despite longstanding international concerns about Pakistan’s use of terrorism as a tool of state policy.

Adding to the misinformation, some members of China’s strategic community have gone so far as to claim that the Pahalgam attack was a false flag operation orchestrated by Indian security forces, further muddying the waters and reinforcing a narrative that diverts attention from Pakistan’s role in the conflict.

Self-Proclaimed Win

Within some segments of the Chinese media landscape, the India-Pakistan conflict has been used as an opportunity to showcase and celebrate the effectiveness of Chinese-made weapons systems supplied to Pakistan. For example, Tianjin Daily ran an article comparing the air power of India and Pakistan, ultimately suggesting that neither side could secure a “decisive victory.” However, other observations took a more victorious tone, highlighting the performance of Chinese equipment such as the J-10C fighter jet, PL-15E missile, and HQ-9 air defense system as superior to their Indian counterparts. These comparisons are often framed as proof of China’s growing technological edge and industrial ability.

A viral video on Chinese social media, reportedly showing an Indian Rafale jet being shot down, has been used to amplify narratives around the success of China’s defense technology and the progress of state driven initiatives like Made in China 2025. This sense of military confidence is echoed across blogs, forums, and social media platforms, where users frequently draw attention to China’s perceived role in shifting the balance on the battlefield.

However, according to the findings from a French intelligence agency, obtained by The Associated Press, defense attachés stationed at Chinese embassies have been actively working to disrupt international sales of the French-made Rafale fighter jet. The report claims these Chinese officials have tried to discourage countries that already operate the Rafale, such as Indonesia, from placing additional orders, while urging prospective buyers to opt for Chinese aircraft instead. A French military official, who requested anonymity along with the unnamed intelligence agency, shared the information with AP.

On the other hand, Chinese scholars and analysts have also weighed in, crediting China’s subtle but firm posture with helping to prevent the India-Pakistan confrontation from spiraling into a larger conflict. Some argue that Beijing’s early support for Pakistan was a strategic move aimed at curbing what they see as a more powerful India from taking overly aggressive steps. This narrative reinforces the idea of China as both a technological leader and a stabilizing force in the region.

The Digital Relay: China to Pakistan to India

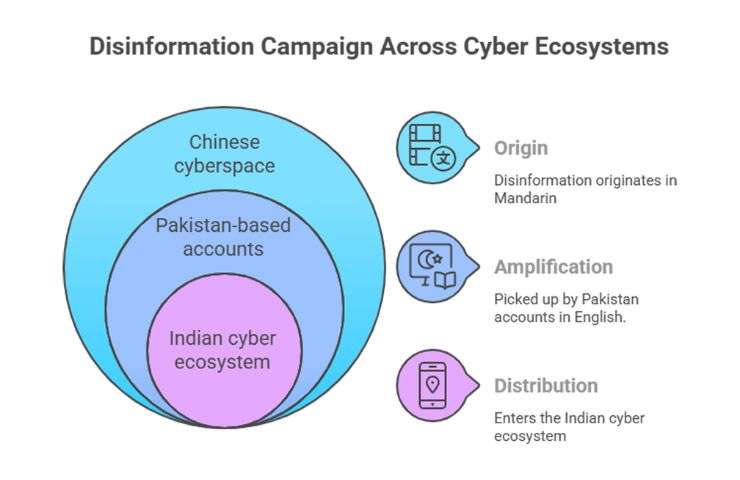

What makes China’s disinformation campaign more potent is its relay mechanism.

The pattern is predictable but effective:

- Disinformation originates in Chinese cyberspace (primarily in Mandarin and regional dialects).

- It gets picked up by Pakistan-based accounts in English.

- From there, it enters the Indian cyber ecosystem, where it’s often mistaken for international news.

This multi-stage relay gives Chinese propaganda a local, organic appearance—making it harder to identify and debunk quickly.

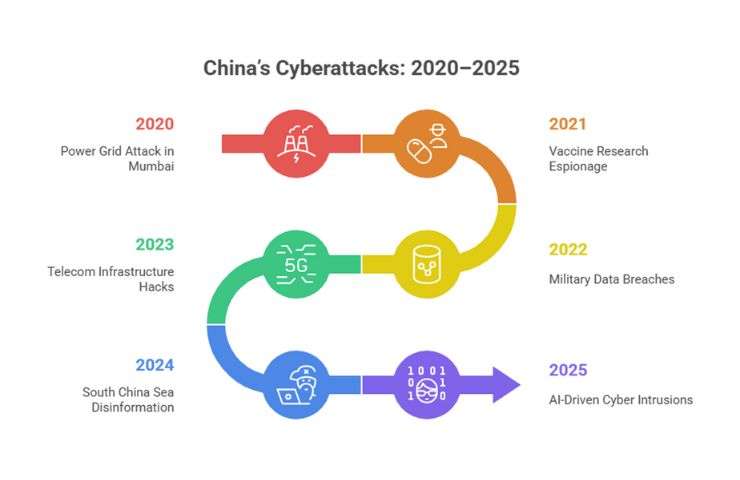

China’s Cyberattacks: 2020–2025

Beyond disinformation, China has been accused of launching sophisticated cyberattacks across sectors in India and globally between 2020 and 2025. Some of the notable incidents include:

These attacks aren’t random—they are part of a long-term strategy aimed at weakening India’s digital defenses while gathering intelligence on sensitive sectors.

Conclusion: The Battle for Minds and Machines

The future of warfare won’t be decided solely by military might—it will hinge on the control of narratives and networks. For China, dominating the cognitive battlefield is as important as seizing physical ground.

India must recognize that cyberattacks and disinformation are not sideshows—they are central pillars of modern conflict. The lessons from Galwan, and from the broader cyber onslaught between 2020–2025, must drive India to build resilient digital and psychological defenses.

Because in the wars of the 21st century, victory may be less about bombs and bullets—and more about bytes and belief.

More News on China – The Kachin Crossroads: China’s Ultimatum and the Global Rare Earth Dilemma