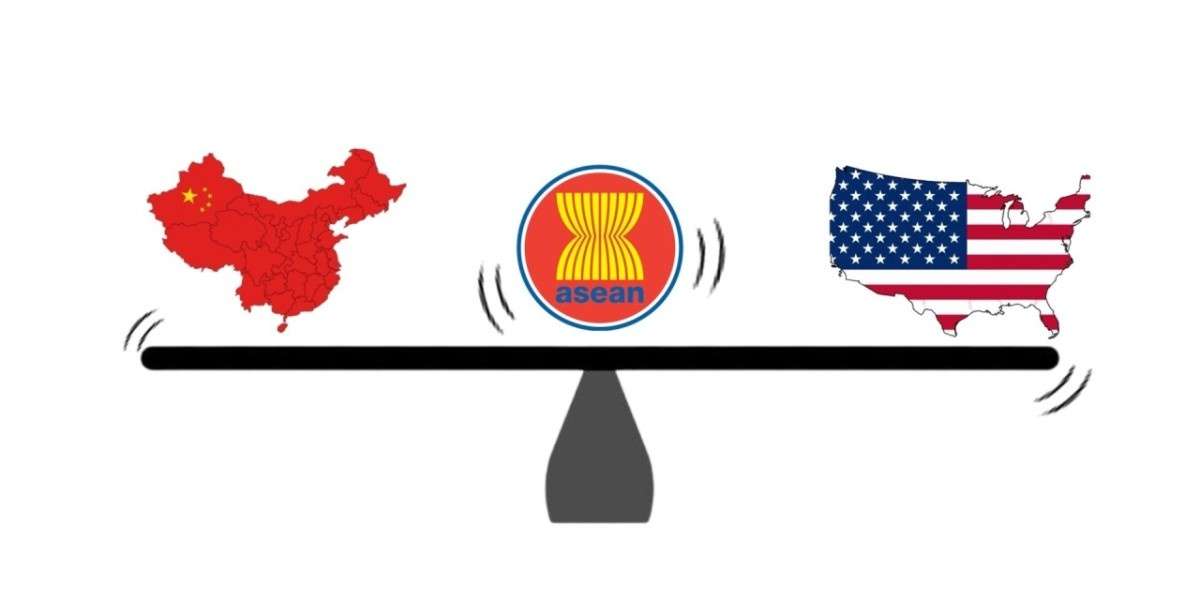

The international trading system is under strain again, and Southeast Asia is stuck in the crossfire of escalating tariffs between United States and China. The United States has become focused on what it sees as “transshipment” of Chinese goods through ASEAN member nations and is pressuring those countries to tighten their own controls and close loopholes allowing goods from those countries to be “deemed” as non-Chinese and avoid tariffs. This reality not only reflects the growing U.S.–China trade rivalry but also reveals the structural vulnerabilities of ASEAN economies, which are highly dependent on foreign-led industrial development.

The Roots of the Transshipment Dispute

The origins of the issue lay in the first Trump administration’s trade war with China. In 2018, the U.S. imposed wide-spread tariffs on Chinese goods, primarily to lessen Beijing’s trade surpluses and perceived unfair practices. Because of the tariffs, many Chinese companies searched for a way to maintain access the U.S. market, and one such method was to relocate production facilities, or at least portions of supply chains, to ASEAN countries like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia.

ASEAN countries welcomed this surge of investment at the outset. Governments offered tax breaks and fast-tracked approvals to lure Chinese companies in hopes of developing jobs and exports. Thailand, for example, offered five-year tax breaks to corporations willing to invest in the country. Vietnam, which was already emerging as a manufacturing hotspot, saw an influx of factories related to China making everything from electronics to textiles.

But what Washington identified was not always genuine industrial relocation. In many cases, Chinese goods were either relabelled as Vietnamese or Thai, transshipped through ASEAN ports, or subjected to minimal processing before being reexported. These practices allowed Chinese products to enter the U.S. market under ASEAN labels, avoiding the higher tariffs that directly targeted Chinese exports.

Washington’s Growing Frustration

The United States quickly became cautious of this trend, especially when they began to see similar trends in trade numbers. Imports from China were significantly increasing to Vietnam at the same time as imports from Vietnam to the United States were increasing, indicating that Vietnam was acting as a conduit for Chinese imports. As of 2025, Vietnam was in the third position among the countries contributing to America’s trade deficit, after China and Mexico. The other ASEAN countries, such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, were ranked high as well. That raised alarms in Washington, where members of the government were blaming ASEAN for tariff evasion.

Peter Navarro, the White House trade adviser and an outspoken critic of China, has now accused Vietnam of “nontariff cheating.” Since then, the Trump administration has become more aggressive, threatening to impose tariffs of up to 40% on Vietnamese imports in the event of transshipment.

Stricter Rules of Origin

One of Washington’s key strategies in this effort is to tighten rules of origin, the measures used to assess a product’s “nationality.” With most FTAs, a product can be regarded as locally made if roughly 40% of its value was added inside the country of export. The U.S. is now pushing countries in the ASEAN region, most notably, Thailand, to increase that threshold to 60%. Such a move would make it far harder for Chinese-linked firms to qualify their goods as ASEAN-made, but it would also force local businesses to restructure supply chains and increase costs. Thailand has resisted, preferring to maintain the 40% standard, but negotiations continue under heavy U.S. pressure.

ASEAN’s Structural Weaknesses

The controversy reveals an underlying issue: ASEAN depends upon foreign companies for its industrial development. In Vietnam, foreign enterprises comprise almost three-quarters of overall exports, while exports account for about 80% of its GDP. This dependency exposes Vietnam to fluctuations in global trade. Although foreign funds have been the engine of rapid growth, they have created fragility in economies. When tariffs are bumped in the U.S., or there is a breakdown in the global supply chain, ASEAN economies feel the effects more acutely. In addition, the focus on cheap manufacturing entails the risk of locking these economies into the “middle-income trap,” where growth stagnates once wage advantages disappear.

Thailand’s experiences demonstrate this perfectly. Even after marketing itself as the “Detroit of Asia,” political instability and coups, plus years of stalling on reforms, have kept the country from moving up the value chain. Meanwhile, while Vietnam emerged with spectacular export growth, its domestic industrial development has lagged, leading to an economy that’s too exposed to external shocks.

Wider Global Implications

The action by the U.S. is not happening in a vacuum. Japan, the European Union, and other partners have also expressed concerns about transshipped Chinese goods, particularly in sectors such as solar panels and steel. Japan has begun developing its own monitoring system for transshipment, responding to complaints from its business associations. International coordination on enforcement has begun to increase, making regulatory loopholes less useful for ASEAN.

Meanwhile, China continues to be ASEAN’s biggest trading partner, with total bilateral investment exceeding $450 billion. As a result, ASEAN governments are forced to tread a fine line by tightening controls to satisfy Washington, but not to alienate Beijing.

The Road Ahead

For ASEAN, the lesson is clear. Continued dependence on foreign-led exports leaves their economies vulnerable to great power rivalries. Developing stronger homegrown industries, investing in technology and human capital, and diversifying markets are essential steps to reduce exposure. For the United States, targeting transshipment is part of a broader strategy to exclude China from global supply chains. But its effectiveness depends on ASEAN’s willingness and capacity to implement reforms. If they fail, Washington may resort to blanket tariffs, which could hurt ASEAN economies as collateral damage.

Ultimately, illegal transshipment is not just a technical issue of labels and shipping routes, it is a symptom of a fragile global trade order. ASEAN countries face a choice: adapt by strengthening domestic industries or risk being perpetual pawns in the U.S.–China contest.