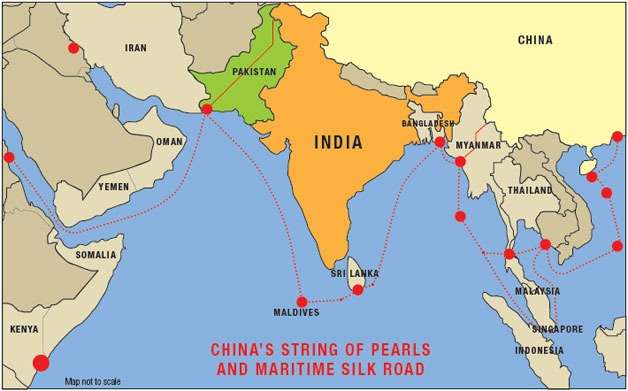

In South Asia, the emergence of three ports – Gwadar (Pakistan), Hambantota (Sri Lanka), and Chittagong (Bangladesh), that are influenced by Chinese leadership have created a stir of strategic concern. These ports make up something that has come to be known as China’s “Triangle of Death.” These three ports form a maritime arc around India’s southern flank. Each port is located at an essential node of the Indian Ocean, which is one of the busiest trade routes on the planet and where nearly 80 percent of the world’s oil supplies transit. From Beijing’s perspective, this triangle represents economic connectivity and logistical outreach. For India, it increasingly appears to be a geopolitical noose tightening around its sphere of influence.

The Gwadar Port in Balochistan, Pakistan is viewed as China’s crown jewel in South Asia in terms of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Run by the China Overseas Port Holding Company, Gwadar provides China with direct access to the Arabian sea, a gateway to the Middle East and Africa. Further southeast, Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka became a litmus test for China’s “debt diplomacy”, when Colombo, unable to repay loans, gave the port to a Chinese state-owned company on a 99-year lease in 2017. The third vertex, Chittagong Port in Bangladesh, though not fully owned or operated by China has made substantial infrastructure investments and has increased operations. Collectively, these three points create what Indian strategists refer to as a maritime containment strategy, a variation of China’s broader “String of Pearls” plan to encircle India’s maritime boundaries with Chinese geography.

China’s Expanding Footprint in the Indian Ocean

China’s aspirations at sea have always been more than about trade. Since the early 2000s, Beijing has focused systematically on ports, pipelines, and bases in the Indian Ocean region, Kyaukpyu in Myanmar to Djibouti on the East African Coast. The objective in each case has been to ensure China’s energy security, extend naval reach, and to create logistics hubs that can serve commercial and military purposes. The “Triangle of Death” is simply the latest example of this activity and its immediate proximity to Indian waters was particularly worrying for New Delhi.

At the same time, Hambantota represents a warning for smaller countries ensnared by China’s debt-trap diplomacy. After falling behind on its repayment obligations for Chinese loans, Sri Lanka essentially gave Beijing control of the port for nearly one hundred years. Hambantota now contains Chinese-built docks and facilities that could be readily repurposed for naval resupply. Its proximity to important waterways, just north of the vital Malacca Strait, provides an opportunity for Beijing to surveil and perhaps manipulate maritime commerce pathways.

China’s involvement in Chittagong is less immediate, but is steadily gaining traction. Through a variety of infrastructure projects, sales of defence goods, and financing to develop “industrial” zones, Beijing is inserting itself further into the economic fabric of Bangladesh. While Dhaka insists that it is cooperating only on commercial terms, a long-standing pattern of China in other parts of the world suggests the foothold Beijing has within the Bangladeshi economy is likely to transform into strategic leverage. Chittagong’s expansion with Chinese financing could potentially grant Beijing access to the Bay of Bengal, just east of India’s Andaman and Nicobar Command, a vital Indian naval stronghold.

The three nodes collectively create a “triangle” or strategic geography for China to surveil, influence, and project its power across the Indian Ocean when required. This network poses a significant threat to India’s traditional hegemony and undermines India’s role as South Asia’s premier maritime security provider.

India’s Strategic Dilemma: Containment vs. Engagement

China’s expanding presence in the Indian Ocean poses an intricate dilemma for New Delhi, it is a dilemma that military deterrence cannot remedy. India benefits from geography: its lengthy coastline and location in the Indian Ocean positions it as the maritime fulcrum. However, China has undertaken its own version of “checkbook diplomacy,” using its wealth to influence India’s neighbours by exploiting their financial needs and developmental aspirations.

India’s short-term priority will be to regain regional trust and influence through active diplomacy, economic alternatives, and partnerships. The Neighbourhood First and the Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) doctrines must move from the realm of rhetoric to concrete action. India should provide additional development cooperation to Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Maldives. Most importantly, India must ensure that it implements its projects quickly and efficiently and, without political overhangs, offer a much more desirable alternative to the opaque terms promoted by Chinese loans.

In terms of defence, India is already making commendable progress. The Indian Navy is increasing its blue-water- capabilities, bringing new warships and submarines into service, and upgrading the facilities at its bases in Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Karwar, and Visakhapatnam, that allow India to conduct robust surveillance and strike capabilities across the Indian Ocean. In addition, India’s contributions to strategic groupings such as QUAD (U.S., Japan, and Australia) bolsters India’s maritime security network and deters unilateral Chinese expansion. India may also utilize its soft power, cultural, educational, and humanitarian, to strengthen relationships with its neighbours.

By contrast to China’s transactional model, India has historical and cultural ties to South Asia that provide India with some advantage Beijing cannot overcome. New Delhi can reposition itself as a friendly power rather than a hegemon by investing in digital connectivity, health infrastructure, and sustainable development.

The Way Forward: Building a Counter Triangle

To counter the “Triangle of Death,” India needs to build its own “Triangle of Stability.” This could rest on partnerships regarding ports in Iran (Chabahar Port), in Sri Lanka (Trincomalee Port), and in Indonesia (Sabang Port). The Chabahar Port is already a counter to Gwadar Port having been developed in collaboration with Iran. It provides India with direct connectivity to Afghanistan and Central Asia while avoiding Pakistan.

Improvement in logistics and cooperation could enhance that route and undermine China’s overall dominance in the Arabian Sea. In the same way, enhancing maritime collaboration with Indonesia and Australia would assist India in expanding its operational footprint from the Bay of Bengal to the South China Sea, effectively countering Chinese encirclement. India’s Information Fusion Centre (IFC-IOR) can also be a critical monitoring agency to track Chinese activity in coordination with like-minded navies to ensure free and open sea lanes. Ultimately, India needs to engage in maritime diplomacy, not only to counter China but to promote a feasible, inclusive narrative for the Indian Ocean. Initiatives such as the Blue Economy, coastal security agreements, and capabilities-building courses for regional navies would help smaller countries view India as a reliable and sympathetic partner, not simply a rival to China