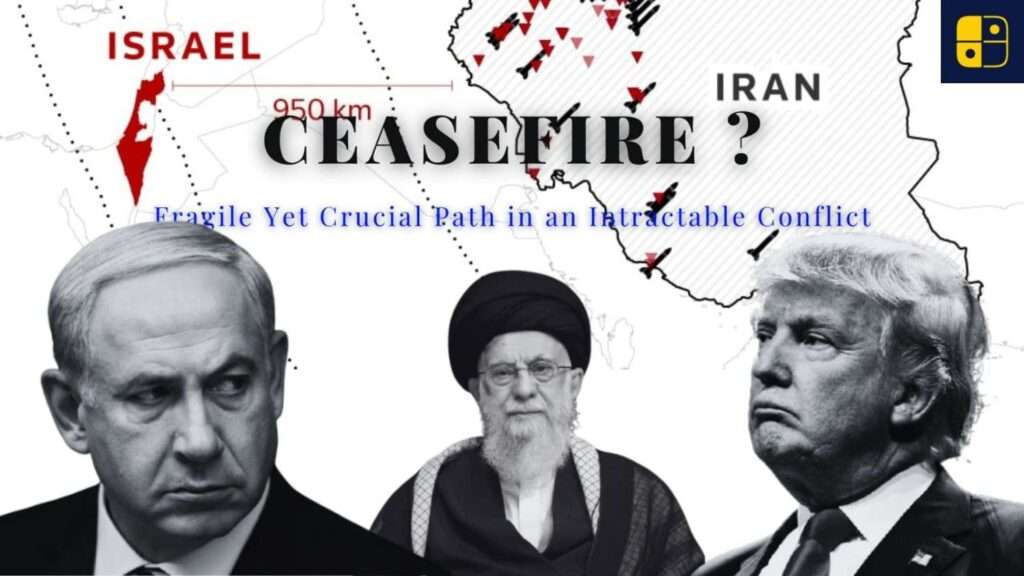

The US and Israel appear to have gone from fiery rhetoric, including talk of assassinating Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, to a ceasefire. This means both sides are starting to figure out how impractical and destabilizing it is to threaten assassination. Initially, the assassination was deemed a “last resort” and a high-risk option following wide-ranging considerations, as it could very well rally anti-Western nationalism across Iran, galvanize anti-American and anti-Israel sentiment, and worsen existing regional instability. The announcement of ceasefire essentially acknowledges the dangers associated with the assassination as well as the precariousness of the region, shifting to an orientation for attempting to de-escalate even under fragmented circumstances.

The Recklessness of Assassination

The discussion around assassinating Khamenei gained prominence through Donald Trump’s posts on social media platforms, where he explicitly hinted at the possibility, stating “we know where he is… but we will not take him out now” and clarifying his intent by using the word “kill”. This reckless suggestion has caused significant consternation. While Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has alluded to such an act potentially ending the conflict, and his defense minister, Israel Kart, has predicted Khamenei would meet the same fate as Saddam Hussein, neither has explicitly stated it as a policy.

Although Ayatollah Khamenei is the Supreme Leader of Iran, he is also the spiritual leader for millions of Muslims, especially Shia Muslims, around the world, including the Shia majorities in Iraq and Azerbaijan, as well as the sizable Shia minorities in India and Pakistan. Iran has responded strongly to these affronts, with Khamenei even claiming in a recorded message, “there is no question of surrender” and that US involvement will “ultimately destroy Israel”.

The potential consequences of such an act are dire. Experts warn that assassinating Khamenei would likely lead to a more radical and angry Iranian population. Iran, unlike many Middle Eastern countries, is an ancient civilization with a strong sense of nationalism and cohesion, not an artificially constructed state. Therefore, killing its leader would not cause the country to fall apart, but rather unite its people in a new nationalistic fervor, even those who may dislike the current government. This could result in a “broken country, a failed state” holding the world’s fourth-largest oil reserves, and would undoubtedly outrage Shia Muslims and Muslim populations globally, leading to widespread disturbances, especially in the Middle East. European allies, recognizing the need for someone to negotiate with, are actively trying to dissuade the US and Israel from even discussing assassination.

Further, the assassination of Ayatollah Khamenei would lead to chaotic anarchy of vast proportions in Iran and beyond. Nationally, it may spawn a surge of Iranian nationalism, across various groups, that is likely to unite even regime critics against what they would see as foreign meddling in their internal affairs and bolster hardliners and even the most hardline elements within Iran. Globally, Shia groups in Iraq, Bahrain, and Lebanon might perceive it as an attack on their religion, prompting protests and violent reprisals. There would be regional consequences as destabilizing events could affect the oil markets and geopolitical tension in the region could heighten, especially in the Strait of Hormuz. In a worst-case scenario, the split between Sunni and Shia populations would widen and ignite new conflicts and proxy wars. Finally, dealing with Iran on nuclear and regional issues would be exceedingly more difficult for the West.

The Illusion of Forced Regime Change

Beyond assassination, the idea of forced regime change looms large. Trump has articulated a demand for “unconditional surrender”, later softening it to an acknowledgement that Iran must simply say “I have had it” with its hostile behavior. He also seeks to impose a “cap, roll, eliminate” formula on Iran’s nuclear program, demanding inspection and the right to destroy any objectionable findings. Netanyahu, meanwhile, has publicly appealed to the Iranian people to “rise in revolt against the Ayatollah,” believing Iran to be weak.

However, the historical record strongly cautions against forced regime change through military means. Scholar Robert Pipe’s analysis in Foreign Affairs magazine indicates that no power since World War I has successfully achieved regime change solely through air attacks, regardless of air superiority. Effective military intervention for regime change typically requires a “hammer and anvil” approach, combining ground forces to corner a target with overwhelming air power. This was seen in the case of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, where rebel forces on the ground coordinated with NATO air power.

Such a “hammer and anvil” strategy is highly unlikely in Iran. The Israelis cannot deploy ground troops there, and even Donald Trump would think twice before committing US troops to Iran. Iran is a vastly larger and more complex country than Iraq, lacking the geographical connections that facilitate military movement.

Lessons from a Graveyard of Interventions

The history of Western-led regime changes in the Middle East provides stark warnings. Emmanuel Macron, the President of France, has voiced strong skepticism, asking, “Does anyone think what happened in Iraq in 2003 was a good idea? Does anyone think what was done in Libya in the next decade… was a good idea?”. He argues that military strikes for regime change lead to “chaos” and that the responsibility is to return to discussions.

The US-led regime change in Iraq in 2003, which removed Saddam Hussein, inadvertently became a “self-goal” for Western power. Despite establishing a democratic Shia-majority government, it destabilized the region, leading Sunni elites and former military personnel to join ISIS, effectively giving rise to the terrorist organization from the ashes of Al-Qaeda. This demonstrates how “unintended consequences can follow you if you try to do radical things in regions you either don’t understand very well or which are not ready for change”.

The Arab Spring interventions in Syria, Libya, and Egypt also resulted in chaos and broken states. Syria endured a decade-long civil war, Libya remains divided, and Egypt, after a brief democratic flirtation with the Muslim Brotherhood, reverted to military dictatorship. These interventions triggered massive refugee flows to Western countries, further destabilizing European politics and contributing to the rise of hard-right parties. Even in Afghanistan, after spending trillions of dollars, the US and its allies ultimately handed the country back to the very power they sought to defeat the Taliban.

Adding to this complexity is the “resource curse”, a phenomenon where countries with vast natural resources but weak institutions and broken politics become unstable. Dictators can exploit these resources to finance their rule, either through bribery or by placating larger powers. Iran’s own history exemplifies this, with foreign intelligence intrigue, including American and British intelligence, leading to assassinations and coups related to oil nationalization attempts, such as the 1953 overthrow of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh. The 1979 revolution, which saw the Shah’s exile and Khomeini’s return, ultimately represented a defeat for Western powers.

To contemplate such radical interventions in Iran today, a nation with a rich history and deep-rooted institutions, is considered “very reckless”. Even if a leader is removed, the underlying religious and cultural structures—the Ayatollah, the mosques, the seminaries, will persist. The lessons from recent history are clear: radical regime change in complex societies often leads to chaos, unintended consequences, and the creation of failed states rather than desired outcomes.

It is very likely that killing Ayatollah Khamenei would cause chaos in the region, anti-Western sentiment could rise dramatically, and the divide between Shia and Sunni communities could widen. The risk of escalation into violent conflict would possibly increase. Rather than the absence of organized violence in the region as a desired state, it is a dangerous decision quagmire with disastrous likely results.